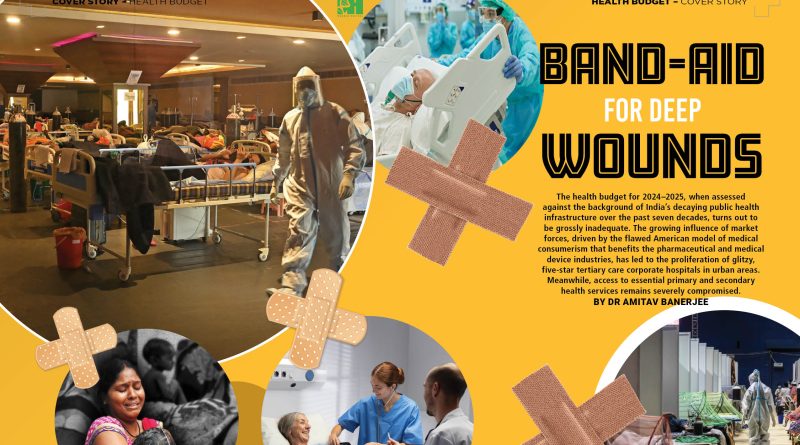

Band-Aid for Deep Wounds

The health budget for 2024–2025, when assessed against the background of India’s decaying public health infrastructure over the past seven decades, turns out to be grossly inadequate. The growing influence of market forces, driven by the flawed American model of medical consumerism that benefits the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, has led to the proliferation of glitzy, five-star tertiary care corporate hospitals in urban areas. Meanwhile, access to essential primary and secondary health services remains severely compromised.

The health budget for 2024–2025, when assessed against the background of India’s decaying public health infrastructure over the past seven decades, turns out to be grossly inadequate. The growing influence of market forces, driven by the flawed American model of medical consumerism that benefits the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, has led to the proliferation of glitzy, five-star tertiary care corporate hospitals in urban areas. Meanwhile, access to essential primary and secondary health services remains severely compromised.

By Dr Amitav Banerjee

The debate surrounding the health budget has become an annual ritual, typically revolving around monetary allocations under various heads. The result of these annual exercises often culminates in blaming the lack of funds for the country’s dismal health indicators.

However, more important than the allocation of funds is the discussion on how we utilise our limited resources to meet the health needs of our large population. Public health priorities are unique to each country and cannot be simply adopted from another or dictated by well-meaning international donors who may be unaware of our specific health needs.

However, more important than the allocation of funds is the discussion on how we utilise our limited resources to meet the health needs of our large population. Public health priorities are unique to each country and cannot be simply adopted from another or dictated by well-meaning international donors who may be unaware of our specific health needs.

Health economics is less about money and more about the judicious allocation of resources, considering the needs and value judgments that often elude quantification in monetary terms. Non-monetary inputs and the decisions based on them can have a more significant impact on the overall health of the population than the total financial outlay in the health budget. There are countries with substantial financial allocations for health, but the outcomes in terms of population health are not commensurate with the money spent.

The USA serves as a case in point. Despite spending more on healthcare than any other nation, Americans remain dissatisfied with their healthcare system. The USA allocates around 15 per cent of its GDP to health, compared to 11 per cent in France and Germany, 10 per cent in Canada, and 8 per cent in the UK and Japan. Most countries in Asia and Africa spend far less, typically around or under 5 per cent of their GDP.

The USA’s experience, characterised by high spending but low efficiency in terms of health outcomes, should serve as a cautionary tale for other countries. Money not used wisely, based on a country’s public health priorities, is money wasted.

The USA’s experience, characterised by high spending but low efficiency in terms of health outcomes, should serve as a cautionary tale for other countries. Money not used wisely, based on a country’s public health priorities, is money wasted.

Several factors contribute to the inefficiency of the US model of health budgeting, particularly the increased consumerism in health driven by market forces—something other countries should heed. Market forces in the US have driven Americans to consume excessive amounts of costly medical care of uncertain benefit. This demand has led to allocation inefficiency, where the incremental money spent in the health budget did not translate into proportional benefits. Advances in medical technology, often overhyped by market forces, have skewed healthcare towards tertiary levels, neglecting primary and secondary care. Medical treatment at the tertiary level is becoming more complex in an attempt to achieve perfection with zero error expectations, leading to increased litigation and eroding trust between patients and doctors. Defensive medicine, involving a battery of often irrelevant investigations to protect against possible litigation, has further escalated the cost of medical care and contributed to allocation inefficiency.

Various stakeholders, including the pharmaceutical and other industries, have entered the fray, seeking returns on their significant investments in R&D. The medical-pharmaceutical industry has transformed healthcare into a monolith with vast resources but poor vision. As a result, primary and secondary care has been neglected in favour of investments in tertiary care. Unhealthy diets and the neglect of physical activity are driving increasing levels of obesity and co-morbidities of non-communicable diseases, which, in turn, lead to a demand for tertiary-level healthcare. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of a healthy lifestyle, not only for the prevention of and reduced morbidity and mortality from non-communicable diseases but also for ensuring that good population-level health can cushion the effects of pandemics. Western countries, including the USA, where overweight rates are two to three times higher than in Asian and African countries, experienced 10 to 20 times higher death rates from COVID-19, despite far higher vaccination rates (most African countries had less than 5 per cent vaccination coverage but did not face the same pandemic severity).

Lessons for India from the American Experience

Lessons for India from the American Experience

There are crucial lessons from the American experience that India can ill afford to ignore. While India began with a sound roadmap for health based on the country’s health problems and priorities, we seem to have lost our way over the years. Increasingly, we are following the American model, dominated by specialists and sub-specialists, pushing first-contact general practitioners into the background, if not into oblivion. Like in the USA, market forces are increasingly influencing our health policies. This can limit the vision for an objective analysis of our health priorities, which may become skewed towards off-the-shelf priorities from other regions or the dictates of the market, resulting in allocation inefficiency. Regardless of how large our health budget is, inappropriate allocations will not improve the health of our population. Unfortunately, these dynamics are already at play. A brief summary of our health vision since Independence and how we have strayed from it will help us understand the nuances.

India began with a sound roadmap for health. Around the time of Independence, the Health Survey and Development Committee, known as the Bhore Committee, outlined India’s public health priorities and made its recommendations accordingly. The Bhore Committee report is vast in its scope and vision, but over the years since Independence, its vision seems to have dimmed.

The Bhore Committee highlighted the poor state of health in India, noting high infant mortality rates (IMR) and short life expectancy. It attributed these issues to unsanitary conditions, inadequate public health infrastructure, poor nutrition, and a lack of general and health education. The Committee stressed the need for a frontal attack on these factors and emphasised the importance of maintaining public awareness and momentum in the fight against disease. It also highlighted the enormous economic losses the country faces due to malnutrition and preventable morbidity and mortality, a value judgment often missing from appraisals of the annual health budget.

In its recommendations, the Committee stated that health services should be an integral part of an overall plan for national reconstruction. Addressing health problems by focusing on a single aspect in isolation, as is the current practice, would only lead to disappointment and a waste of money and effort. The Bhore Committee envisioned a primary health unit for every 10,000 to 20,000 people, with a 75-bed hospital staffed by six medical officers, including specialists in medicine, surgery, and obstetrics and gynaecology, supported by other auxiliary staff. About 30 primary units were to be overseen by a secondary unit with a 650-bed hospital offering all major specialties. At the district level, it recommended a 2,500-bed hospital providing primarily tertiary care.

Even after 77 years of Independence, despite achieving the status of the world’s 5th largest economy and having 200 Indians on the Forbes 2024 billionaires list, India ranks 111th out of 125 countries in the Global Hunger Index. It ranks among the countries with the highest rates of child malnutrition and anaemia. An estimated 4,500 children under five die daily in India from preventable diseases, exacerbated by malnutrition.

Among communicable diseases, India accounts for a quarter of the global burden of tuberculosis (TB), with over 1,400 Indians dying daily from the disease. Dengue, Chikungunya, Zika, Japanese Encephalitis, malaria, and other vector-borne diseases are rampant in the country. It is embarrassing that we have not yet reached the level of health that developed countries had achieved before the start of the Second World War.

How Did We Stray from the Path Laid Out by the Bhore Committee?

Former Professor at AIIMS New Delhi, Dr Bidhu K Mohanti, an oncologist, states that the Indian healthcare system has passed through three stages: 1952–1980; 1981–1992; and 1993 to the present.

In the first 30 years after Independence, in line with the Bhore Committee Report, health services, in addition to private general practitioners, were mostly provided by salaried government doctors within a three-tiered public health infrastructure at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. The primary and secondary levels of healthcare at the village, taluk, and district levels were designed to treat the majority of diseases and also provide preventive and health promotion services free of cost.

The next decade saw the gradual decay of the public health infrastructure due to the overall economic collapse. Government spending on medical education, which had previously been its sole responsibility, stagnated. Several private medical colleges were established in the 1980s, beginning with the southern states, after which there was no looking back. Currently, half of the medical colleges in the country are private. Similarly, public hospitals faced a resource crunch, and to cope, a number of public-private partnerships evolved.

Big Tectonic Shift After 1992

There was a paradigm shift in the economic model after 1992, triggering enormous changes in the health financing system that have spilled over into the 21st century—a complex, hybrid model of healthcare delivery with no clear vision and increasing influence of market forces. The emphasis that the Bhore Committee Report placed on the neglected aspects of public health, which have led to large amounts of preventable morbidity, has become the underbelly of our shining reputation as the favoured country for medical tourism, due to our five-star tertiary care corporate hospitals offering state-of-the-art medical treatment.

Market forces, a necessary evil in an era of massive technological investments in R&D for drug discovery and medical devices, have transformed medicine into an industry. In chasing the glitz and glamour of the high-tech medical industry, we have strayed faster and further from the roadmap of the Bhore Committee, which had envisaged: (a) a hospital with 75 beds for every 10,000 to 20,000 people as a primary health unit at the rural level, (b) a 650-bed secondary multi-specialty hospital at the taluk or sub-division level, and (c) a 2,500-bed tertiary-level hospital in each district.

In post-1992 economically liberated India, with its emphasis on GDP growth and increasing privatisation of health services, there has been a failure to allocate adequate resources to meet the demands for a robust public health infrastructure. In this vacuum, private entrepreneurs have thrived. More than 60 per cent of outpatient attendance, 70 per cent of hospital beds, and 80 per cent of doctors are now in the private sector. Medical and nursing education, which lays the foundation of the healthcare system, has witnessed increasing private investment with government approvals. It is debatable whether these developments can someday meet the healthcare needs of the country, particularly for the poor and marginalised.

From time to time, the government does make attempts to address the long-neglected public health infrastructure, which is accessible to the less privileged who cannot afford private healthcare. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) launched in 2005 was the forerunner of the more ambitious National Health Mission (NHM), which has two components: the NRHM and the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM). While these programs were well planned, their execution has been a challenge. The recent budget also has given stepmotherly treatment to the NHM.

Another attempt to offer affordable health services to the poor was the Ayushman Bharat Programme (ABP) launched in 2017 and included in the health budget of 2018-19. The ABP had two components: first, the delivery of comprehensive primary-level healthcare by upgrading 150,000 health Sub-Centres (SC) and Primary Health Centres (PHC) to Health and Wellness Centres (HWC) by the year 2022, and secondly, providing secondary and tertiary-level medical care under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY). It was claimed that PMJAY is the world’s largest health programme. Paradoxically, no significant financial provisions were made to beef up the ailing public health infrastructure in the country.

The Finance Ministry allocated Rs 1,200 crore for the health and wellness centres in 2018-19, which translates to Rs 80,000 per centre. Essentially, it was just a thin coat of paint for the old primary healthcare centres, which were renamed for the occasion. The budget allocation for PMJAY at its launch in 2018-19 was Rs 2,000 crore, which was twice the previous year’s budget for the Rashtriya Swastha Bima Yoyana, PMJAY’s predecessor, which was absorbed into the PMJAY.

Essentially, both components of the Ayushman Bharat Program—the HWCs and the PMJAY—amounted to shuffling the same deck of cards, only with a shiny new cover. Both these schemes covered breadth but lacked depth.

Health Budget 2024-2025: Falling Short of Meeting the Needs of the Public Health Infrastructure

The health budget for 2024–2025, when appraised against the background of our decaying public health infrastructure over the past seven decades, seems like a misplaced band-aid over the deep wounds our public health system has suffered over the years.

The budget has allocated Rs 90,958.63 crore to the Union Health Ministry, a 12.9 per cent increase from Rs 80,517.62 crore in the revised estimates for the Health Ministry in 2023-24. Of this, Rs 87,656.90 crore has been allocated to the Department of Health and Family Welfare and Rs 3,301.73 crore for health research. The budget for AIIMS New Delhi has been increased marginally from Rs 4,273 crore to Rs 4,523 crore.

The government has also announced customs duty exemptions on three cancer treatment drugs and has reduced customs duty on X-ray tubes and flat panel detectors.

The marginal extra allocations may appear to signal a slow but steady focus on our health, but they hide the truth that these allocations fall woefully short considering the enormity of the country’s health challenges and the unfulfilled promise of the Bhore Committee Report, which was tabled around the time we had our “tryst with destiny,” as our first Prime Minister famously coined it.

Straying from the Bhore Committee’s Path

A paradigm shift in the economic model after 1992 triggered enormous changes in the health financing system, resulting in a complex, hybrid model of healthcare delivery with no clear vision and increasing influence from market forces. The Bhore Committee Report, which emphasised neglected aspects of public health and aimed to address preventable morbidity, has been overshadowed by India’s reputation as a favoured destination for medical tourism, featuring high-end tertiary care corporate hospitals offering state-of-the-art treatment.

The Health Budget for 2024-2025, when assessed against the backdrop of a deteriorating public health infrastructure over the past seven decades, seems like a misplaced band-aid over deep wounds. The budget has allocated Rs 90,958.63 crore to the Union Health Ministry, a 12.9% increase from Rs 80,517.62 crore in 2023-24. Of this, Rs 87,656.90 crore is for the health and family welfare department and Rs 3,301.73 crore for health research. The budget for AIIMS New Delhi has increased marginally from Rs 4,273 crore to Rs 4,523 crore.

Criticisms of the budget, however, can also miss the mark. For instance, concerns about the lack of incentives for industry to bring private healthcare closer to common Indians overlook the absence of private hospitals in rural areas where most of the population resides. There are no shortcuts to establishing public hospitals in rural areas, which would require substantial investments to rectify years of neglect.

Another criticism is the failure of the NHM to roll out a nationwide cervical cancer vaccination programme as announced in the interim budget. This critique is misplaced, reflecting an amateurish approach to public health priorities. Even Rajya Sabha Member Smt Sudha Murthy, in her maiden speech, urged the government to launch the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for girls. However, this proposal highlights how health policymakers, influenced by market forces and celebrity endorsements, are distanced from ground realities.

The HPV vaccine’s rollout should be approached with caution. Previous vaccine trials in India, sponsored by the Gates Foundation and conducted by PATH, encountered ethical issues, including deaths during the trials. An investigation by the 72nd Joint Parliamentary Committee revealed irregularities and questioned the ICMR’s promotion of the vaccine without proper study. Despite this, policymakers continue to promote the HPV vaccine, driven more by propaganda than scientific evidence.

Furthermore, a recent paper in the Journal of the Royal Society questioned the vaccine’s efficacy, noting that trials were not designed to detect long-term cancer prevention, and follow-ups were limited. Another paper published in BMC Cancer indicated a significant decline in cervical cancer incidence and deaths in India over the past three decades.

If policymakers and philanthropists genuinely aim to prevent cervical cancer deaths, they should focus on making hospital services more widely available as envisioned by the Bhore Committee. This approach, emphasising cervical cancer screening rather than the uncertain HPV vaccine, would be more effective. An analysis from Australia suggested that the HPV vaccine is not cost-effective in settings with established cervical screening.

The NHM, a weak attempt to improve health services for the vulnerable, received just a 1.16% increase in funding, including the ill-conceived HPV vaccination programme. The path forward requires many steps backward—expanding public health infrastructure across the country. The increasing number of high-rise hospitals in big cities indicates that course correction has not yet begun.

Private players are crucial in the health sector, but excessive reliance on them, with their inherent conflicts of interest, will further neglect public health hospitals and centres. Our health planners appear influenced by the flawed American health model of medical consumerism, benefiting the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. A balanced approach, focusing on primary and secondary healthcare, is needed to prevent people from ending up in costly tertiary hospitals.

Ultimately, we must revisit and implement the Bhore Committee’s recommendations. This task is neither glamorous nor lucrative compared to promoting medical tourism, high-rise hospitals, and pharmaceutical products. Until then, annual Health Budget debates will remain futile exercises with minimal impact on public health, despite increased budgets. Effective planning based on scientific evidence and the needs of the people is more crucial than simply increasing funding.

(The author is a renowned epidemiologist and currently a Professor Emeritus at DY Patil Medical College, Pune.