Do mutants create the monsters?

Mutant variants of the novel Coronavirus is creating panic globally. The latest, Delta variant is in the news. Popular perception is that mutants beget monster……

Mutant variants of the novel Coronavirus is creating panic globally. The latest, Delta variant is in the news. Popular perception is that mutants beget monster……

By Dr Amitav Banerjee

A former Chief Minister of an Indian State got into trouble when he remarked, “Coronavirus also has a right to live!” He was trolled heavily on social media. David Deutsch in his provocative book, “The Beginning of Infinity,” states that when we seek explanations, we lean towards anthropocentrism, explaining things parochially from the human perspective.

To balance this is “The Principle of Mediocrity,” which assumes that there is nothing significant about humans in the cosmic scheme of things. One does not know whether the former Chief Minister had read this book. Politicians have little time for reading. But he had made a point keeping with “The Principle of Mediocrity,”

Darwin’s laws of natural selection tell us otherwise. Coming back to the “faux pas” of the former chief minister, viruses also have a right to live. Whether we like it or not nature grants them a fair chance. To survive they follow nature’s way of adaptation – Darwin’s Law. These adaptations are by way of mutations, natural phenomena, not new, due to errors during replication, and occasionally due to selection pressure.

According to principles of successful parasitism, this adaptation is beneficial to both the virus and humans. Errors that make the virus fittest for survival propagate while others lose out due to natural selection. Lethal or virulent strains perish with the host leading to a dead end infection. Lesser virulent ones which do not kill but cause symptoms also do not go far because patients resort to self isolation.

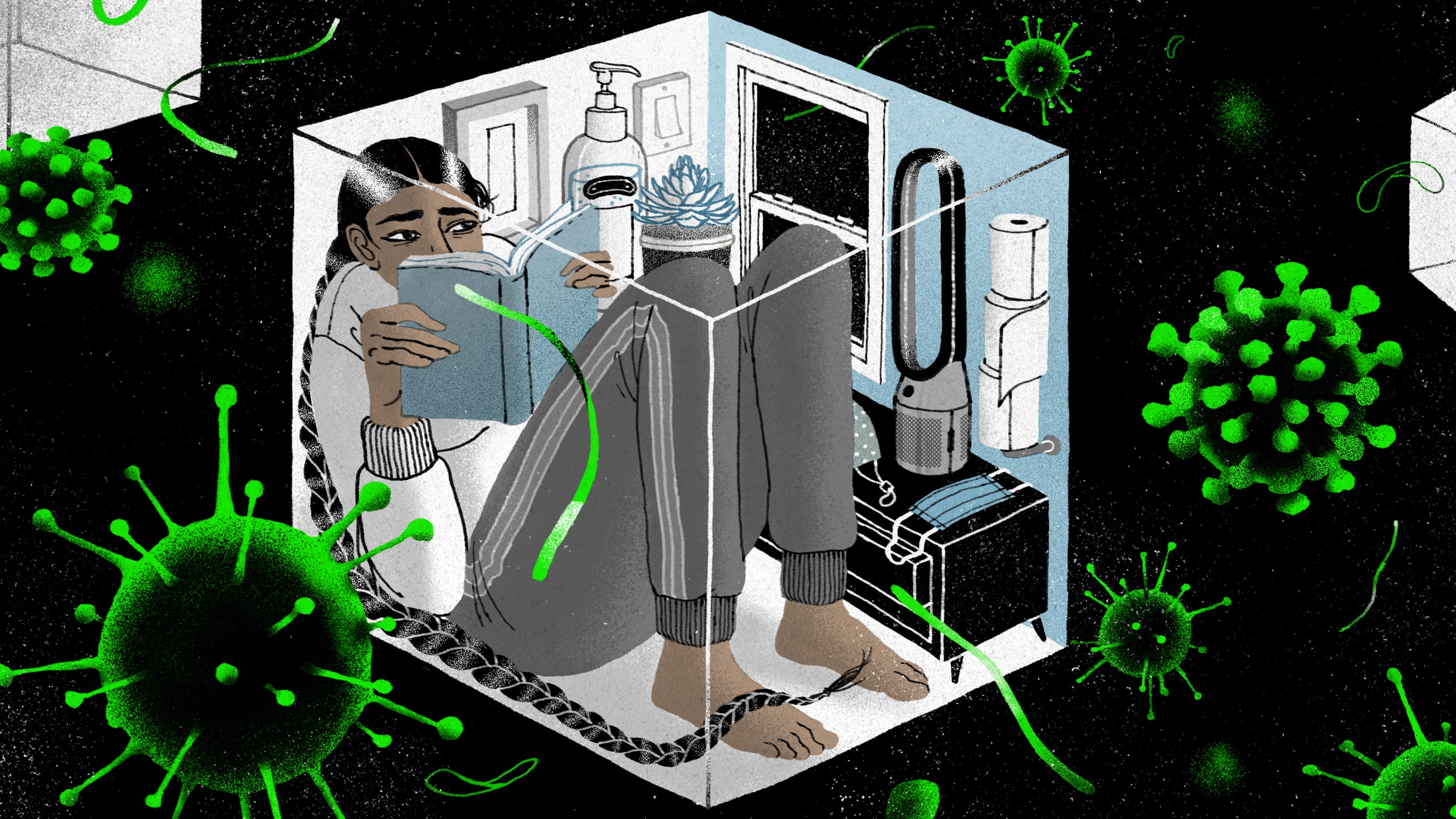

The mutant strains, which survive, are less virulent which do not kill the host, produce very mild symptoms or none at all. People infected with such mild variants will mix with others and transmit widely. The high contagiousness does not necessarily translate to high lethality directly. Such strains promote population immunity with minimum casualties. Towards this goal the novel Coronaviruses is also constantly mutating leading to variants even as this piece is written.

A note of caution, while it may be reassuring that variants may be less lethal in spite of high transmissibility, rapid surge in cases overburdening the health infrastructure may cause higher fatality due to inadequate care. How does mutation take place? The novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is a RNA virus, which has about 30, 000 base pairs of nitrogen compounds, about 3000 to 4000 are in the spike protein. These base pairs can be considered as the building bricks of the virus. Addition, deletion or changes in sequence within these building blocks lead to mutation.

What can be the implications of mutation? There are a number of possibilities. Most mutations have no impact on virulence or infectivity. They are used as fingerprints for tracing the path of outbreaks. Some mutations will become less virulent but more infective, with better chances of survival and propagation by law of natural selection. And rarely, they may become more virulent, such outliers would also lose the evolutionary race. The following are the concerns related to mutation.

What can be the implications of mutation? There are a number of possibilities. Most mutations have no impact on virulence or infectivity. They are used as fingerprints for tracing the path of outbreaks. Some mutations will become less virulent but more infective, with better chances of survival and propagation by law of natural selection. And rarely, they may become more virulent, such outliers would also lose the evolutionary race. The following are the concerns related to mutation.

Will vaccine work? Will immunity obtained after recovery from natural infection work? Will RT-PCR detect the mutant variants? Antibodies and immune cells generated by natural infections or vaccination act on some of the building blocks known as epitopes. As mentioned the novel Coronavirus has about 30,000 base pairs or building blocks of nitrogen compounds. During mutations only a few of the building blocks undergo change. So antibodies and immune cells primed against the whole virus as on recovery from natural infection or immunization by a vaccine derived from the whole virus have very good chance of neutralizing these variants.

Conceptually vaccine derived from whole virus like the Covaxin should offer protection against the variants. However, this has to be confirmed by actual performance against present and future variants. Some vaccines target only the spike protein or more specifically few of the building blocks in them. These targets are known as epitopes, out of 3000-4000 of these base pairs in the spike protein. If mutation occurs in an epitope in the spike protein there is slightly more chance of 3 antibodies and immune cells hitting a blank on a mutated epitope. However, as many epitopes are involved in the process, such vaccines will also confer some protection against the mutants. The RT-PCR tests which target a number of epitopes should also detect variants. Against these principles we may consider the impact of the currently circulating variants. While the delta variant was circulating for past few months in India, it is making headlines now because it is presently circulating in UK causing a small surge in cases in spite of vaccine cover to over 60-80% of the population.

The delta variant was first detected in Maharashtra in October 2020. It has 50% more transmissibility with higher viral load shedding facilitating this. We may assume that this caused the vicious second wave in India. This may explain its very steep rise, infecting four times more people than the first wave at its peak, and an equally sharp fall due to rapid exhaustion of the susceptible (those who had not encountered the virus before), and perhaps widespread and quick generation of herd immunity. Within a couple of months the RT-PCR positivity rates came down from 25% to below 5%.

Vaccination cannot explain this phenomenon as it had no time to catch up, with less than 5% of Indians fully vaccinated during the rise and fall of this wave. Was the population level immunity acquired during the first wave adequate to withstand the onslaught of the second wave? The Covid experience in two big cities in Maharashtra, the frequent epicentres of the pandemic in India, would suggest so based on ecological and individual level data. In the first wave, the worst affected were mostly the slums and tenements while the middle class and affluent who could observe “Covid appropriate behaviour” and “work from home,” were spared.

According to a news, sero-prevalence after the first wave in three slums of Mumbai demonstrated high levels of IgG antibodies around 57% compared to 16% among residents of middle class housing societies. During the second wave, the occupants of the middle class housing societies were mostly affected, while the slum dwellers reported few cases. This suggests that, in the cities, antibodies developed after the first wave protected the people from the lower socioeconomic strata from the fury of the 4 second wave. The second wave also took a toll of the rural hinterlands which were spared in the first wave leaving villagers vulnerable. The same pattern was observed in the industrial twin townships of Pimpri-Chinchwad, in Pune District. Just at the end of the first wave in October 2020, our team undertook a serosurvey on a random sample of 5000 individuals over 12 years of age representative of the 27 lakh population of this town in Pune.

We found overall 34% of the population had antibodies against the Coronavirus. However, this was not homogeneously distributed. There was wide variation of seropositivity between slum dwellers and residents of housing societies. Some of the slums had 70-75% seropositivity while few housing societies had as low as 4-8%. During the second wave we noticed that the regions which had the highest seropositivity after the first wave had the lowest reported cases. In June 2021, we contacted 1081 participants who had IgG antibodies to ascertain reinfections. Out of these only 13 (1.2%), got re-infected with Covid-19 during the second wave, in spite of most of them living and working in densely crowded conditions.

The preliminary findings are reassuring that prior infections with the earlier variant gives sufficient protection against the delta variant. What about lethality of the delta variant? According to a report in first post dated April 07, 2021, the case fatality rate in the second wave at 1.3% was lower than the case fatality rate of 3.6% in the first wave during April 2020. While one reason may be better understanding of clinical management with time, the lethality of the delta strain appears to be lower than previous strains. This is also what one might expect according of evolutionary theory of natural selection as described earlier. What about efficacy of vaccines against the delta variant?

As mentioned above whole virus vaccines may theoretically confer better immunity against present and subsequent variants as mutations occur in only few epitopes. Extensive mutations will kill the virus. However, long term monitoring and follow up should continue to confirm this presumption. 5 Presently, vaccines have been rolled out to less than 15% of our population. The UK experience, with vaccination coverage in the range of 60-80% with the delta variant circulating in the country, may offer some clues. Daily cases in UK are slowly rising in spite of high vaccination coverage. On 02 May 2021 only 1621 new cases were reported. This has risen to 11007 as on 17 June 2021 with last 7 days increase of 33.7% compared to previous 7 days. From 11 June to 17 June 2021 there were 78 deaths showing an increase of 41.8% compared to preceding 7 days. Closer monitoring of the unfolding trends in UK would provide vital clues about the potential of vaccine escape due to the delta variant.

If cases and deaths keep rising in UK in spite of widespread vaccination, other countries should pause to reconsider whether to go for mass vaccination at huge cost or go for focused vaccination of high risk and vulnerable groups. Mutations and variants will be an ongoing phenomenon, thousands of them have already occurred since the origins of this virus. Only few of them are considered “variants of concern” as these may have potential of escaping the vaccine and rarely, immunity acquired from earlier infections. However, these mutants will be less virulent. This is the way of all pandemics. Over time they become seasonal minor illnesses.

(The author is MD, Clinical Epidemiologist, Professor and Head, Department of Community Medicine, Dr D Y Patil Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Pune)