Approaching The End Game

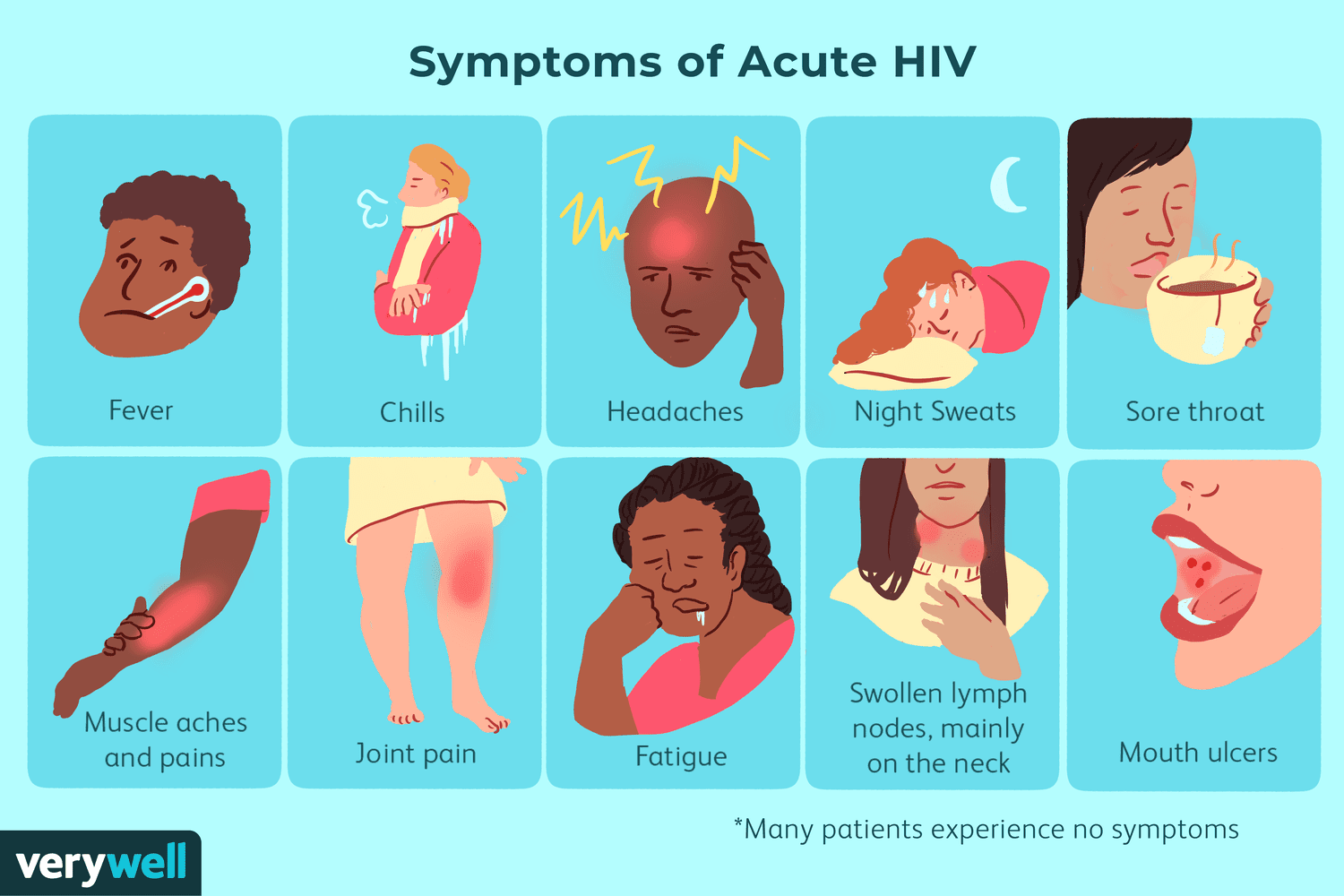

From encouraging declines in prevalence to spikes linked to tattoo exposure and intravenous drug use, the challenges in combating the HIV pandemic by 2030 necessitate a comprehensive strategy, recognising not only medical aspects but also socio-cultural factors that shape its course.

By Dr Amitav Banerjee..…

A review of HIV/AIDS trends is quite encouraging. According to estimates by the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) and the ICMR-National Institute of Medical Statistics, there has been a steady decline in the estimated HIV prevalence in the age group of 15-49 years since the peak of the pandemic in 2000. The prevalence was 0.55% in 2000, which fell to 0.32% in 2010 and 0.21% in 2021. However, there are geographical variations.

A review of HIV/AIDS trends is quite encouraging. According to estimates by the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) and the ICMR-National Institute of Medical Statistics, there has been a steady decline in the estimated HIV prevalence in the age group of 15-49 years since the peak of the pandemic in 2000. The prevalence was 0.55% in 2000, which fell to 0.32% in 2010 and 0.21% in 2021. However, there are geographical variations.

The North-Eastern states of the country continue to bear a higher burden of HIV, with 2.70% in Mizoram, 1.36% in Nagaland, and 1.05% in Manipur. Following closely in prevalence are the Southern states: 0.67% in Andhra Pradesh, 0.47% in Telangana, and 0.46% in Karnataka. The number of people living with HIV (PLHIV) is presently around 24 lakhs. Maharashtra is at the topmost position in the list of states with a significant HIV burden, followed by Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka. Is this due to better survival rates or higher rates of detection? Perhaps both.

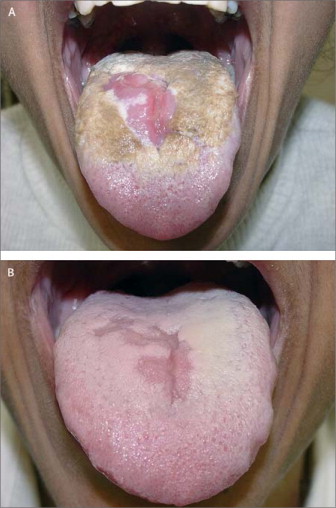

Many blind turns and roadblocks persist as we speed towards the AIDS End Game…India’s commendable role in combating the HIV pandemic is evident through its efforts to make antiretroviral therapy (ART) accessible and affordable to over 95% of PLWHIV. ART, which significantly reduces viral load within a few months, has been a game-changer, interrupting transmission and making HIV a chronic, manageable condition. Regular surveillance and monitoring have further contributed to transforming HIV into a condition that can be effectively managed, enabling PLWHIV to lead normal lifespan.

However, the final stretch towards achieving global goals of zero new infections, zero deaths, and zero discrimination against PLWHIV by 2030 faces numerous blind turns and roadblocks. Straightforward mathematical models alone may not provide an accurate compass to navigate these challenges.

The obstacles include diminishing funds for HIV control, complacency, and interruptions in elimination efforts due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The epidemiology of HIV is inherently complex, with many critical determinants often overlooked.

Understanding the epidemiology of HIV is as intricate as that of any sexually transmitted diseases. Both HIV and STDs are prevalent among individuals with high-risk behaviours, leading to significant heterogeneity in population-level risks. Moreover, societal taboos and stigma associated with sexual behaviour make accurately capturing this major determinant elusive. Consequently, mathematical models for HIV and STDs may deviate from reality.

In addressing the challenges ahead, it is crucial to acknowledge the multifaceted nature of the HIV pandemic, taking into account not only medical aspects but also the socio-cultural factors that influence its trajectory. A comprehensive and nuanced approach will be essential in surmounting the remaining obstacles on the path to achieving the ambitious global goals for HIV by 2030.

In addition to being a sexually transmitted infection, the HIV virus can also spread through the use of unsterilised needles and unsafe blood transfusions. Intravenous drug abuse, particularly in the North East and potentially in other parts of the country, is identified as a significant risk factor for HIV transmission. Similarly, Hepatitis C virus is primarily transmitted through contaminated needles and sharps, often associated with intravenous drug abuse. The stigma surrounding drug abuse and the legal implications of both drug use and trade pose challenges in accurately estimating the true prevalence of these risk factors, often leading to them being ignored or overlooked.

Can these infections spread through the trending practices of tattooing and body art?

While there are some concerns on theoretical grounds that tattoo and body art, which are becoming fashionable, can transmit infections like HIV and Hepatitis C & B, the risk by this mode is negligible if adequate sterile precautions are observed. However, the risk increases if the previous customer had these viral infections with a high viral load.

The transmission risk through body tattooing becomes more significant if piercings are done outside of regular parlours under unhygienic conditions. This includes mass tattoos performed by amateur artists, tattoos done in prisons, and piercings done by friends. A study from Ethiopia has demonstrated that improperly sterilised sharp instruments can transmit HIV and other blood-borne infections like Hepatitis C and HIV. This finding is relevant in the context of India, where there is a lack of regulation for body art and piercing studios, unlike in Europe and the USA, where agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration regulate these practices. As of now, there is no similar provision in India.

Concerns on recent spikes of HIV infection in some parts of the country, some associated with tattoo exposure other with increasing IDUs.

There have been reports that recently some states are witnessing a spike in HIV infections. In Haryana, a recent report highlights that the state has witnessed a surge in HIV infections, reporting over 100 cases in the past two years. The majority of infections were associated with high-risk sexual behaviour followed by tattoo exposure. The demographic most affected includes individuals aged 22 to 43 years, with 56% males, 40% females (including children), and 4% transgender individuals. The districts most impacted were Gurugram, Hissar, Palwal, Pataudi, and Rohtak, which have experienced rapid urbanisation due to the establishment of industrial estates.

Haryana also faces a high transmission of Hepatitis C, primarily through the sharing of needles among intravenous drug users (IDUs). This underscores the need for in-depth research into these behaviours, especially among the youth. The increasing trend of Hepatitis C in any region should prompt further investigation into IDU practices.

Haryana also faces a high transmission of Hepatitis C, primarily through the sharing of needles among intravenous drug users (IDUs). This underscores the need for in-depth research into these behaviours, especially among the youth. The increasing trend of Hepatitis C in any region should prompt further investigation into IDU practices.

In the North East, which has long been a reservoir for both Hepatitis C and HIV, recent instability in Manipur may have contributed to an increase in intravenous drug use. According to the Assam State AIDS Control Society, the region has recorded a threefold rise in HIV-positive cases in the last three years, with an increasing trend in IDUs spreading the virus. The number of HIV-positive cases detected rose from 1,288 in 2020-21 to 4,108 by 2022-23.

Informal discussions with experts involving youth in schools and colleges suggest an increasing trend in experimentation with sex, drugs, and body tattoos across the country. There is a need for a qualitative understanding of these taboo topics by harnessing the expertise of social scientists.

A survey conducted a couple of years ago revealed that eight states, both in the north and the south, have a higher prevalence of intravenous drug users (IDUs) than Manipur and Nagaland. This challenges the prior perception that intravenous drug abuse was primarily an issue in the North East. It serves as a wakeup call to address the broader scope of the problem.

Coping with the current situation requires understanding the psychosocial dynamics contributing to the spike in HIV transmission becomes crucial. Therefore, a social science approach is essential alongside the use of ART in our toolkit. The availability of effective anti-HIV drugs can influence psychosocial dynamics, potentially leading to increased risk-taking behaviours. Studies have shown that widespread access to ART has coincided with resurgence in high-risk behaviours. In this context, there is a need for greater efforts to promote safe behaviour, as success in curative medicine should not lead to the neglect of preventive medicine.

Addressing the psychosocial aspects of the current situation involves not only medical interventions but also comprehensive strategies that consider the societal, cultural, and psychological factors influencing behaviour. Collaboration between health professionals, social scientists, and community leaders is crucial to develop effective preventive measures and promote a holistic approach to tackling the complex challenges associated with the spike in HIV transmission.

An empathetic approach is recommended instead of being judgmental and implementing harsh measures which cannot be sustained.

How to approach drug addicts?

When it comes to approaching drug addicts, it’s crucial to recognise that HIV, drugs, and sex are often surrounded by taboo, stigma, and discrimination. Individuals in such predicaments may hesitate to seek counsel and may go untreated due to fear of judgment. Overcoming addiction is a challenging journey that requires time and effort. Drawing from experiences as a military epidemiologist, especially working with recovered IDUs in Northeast India, it becomes evident that well-intentioned measures by administrators can sometimes exacerbate the situation.

For instance, in the past, when it was recognised that the HIV pandemic was driven mainly by IDUs in some regions of Northeast India, attempts were made to curb the use of intravenous drugs by making needles inaccessible to the general population. However, this approach lacked an understanding of the intense cravings and withdrawal symptoms experienced by addicts. Faced with these challenges, individuals resorted to begging, borrowing, or even stealing to satisfy their cravings, leading to an increase in the use of shared needles and, consequently, driving HIV transmission.

It’s fortunate that many countries now implement the needle exchange program advocated by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), allowing IDUs to exchange their used needles with clean, sterilised ones. Providing empathetic and non-judgmental counselling about this program is crucial, as many IDUs may not be aware of it and could continue using shared needles. Moreover, there may be individuals who are closet addicts due to stigma, making approaches through snowball tracing necessary.

When it comes to delivering sex education, particularly in schools and colleges, it requires innovative and skilful methods. In many Indian families, talking about sexual matters is still considered taboo, and it’s important to destigmatise sex while conveying the hazards of unsafe and promiscuous sexual relations.

An example of a novel and impactful approach to sex education was demonstrated by Dr Ishwar Gilada, who initiated India’s first AIDS clinic. During a workshop on HIV/AIDS at the Governor’s residence in Lucknow in 1997, Dr Gilada used innovative methods to engage participants. He displayed pictures of various positions of sexual union from the Indian classic, Kamasutra. While some may have been scandalised at first, the presentation included a prominent caption with the message, “Many positions with one, instead of one position with many!” This creative method effectively conveyed a crucial message and left a lasting impact. Even after two and a half decades, the memory remains vivid.

Innovative approaches like this not only break the ice surrounding discussions on sexual matters but also make the educational content more memorable and engaging. Such methods can contribute to creating a more open and informed environment for discussions around sexual health and relationships.

How to deal with “marginalised” and “stigmatised” groups?

Any new infection creates panic fuelled by media. Anyone having the infection or even suspected to have the infection is stigmatised and shamed. It happened with HIV/AIDS and more recently, it happened with Covid-19. The stigma and marginalisation can extend to particular groups. This can drive the pandemic underground as such people shy away from the mainstream acting as unattended reservoirs of infection. In the early days of the AIDS pandemic, men having sex with men (MSM) or gay people faced such a predicament.

Roger Detels, Distinguished Research Professor of Epidemiology, at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and the Editor of the classic Oxford Textbook of Public Health, among his many research works studied the natural history of AIDS. He began in research in HIV/AIDS in 1981 studying the natural history of the disease in young gay men, the largest study of its kind in the world.

When he began his study, in the early eighties, the stigma and hostility towards the gay population identified as the cause of the curse was at its peak. Naturally the gay community turned a cold shoulder towards researchers.

During his visit to India in 2002, at a workshop for researchers at AIIMS, New Delhi, I heard him narrate how he overcame this barrier. Besides, interacting with members of the gay community for data collection, which came much later, he looked after them in sickness by arranging treatment, socialised and mixed with them, greeting them on their birthdays and other occasions, shared with their good moments, and comforted them in grief. He cared for them as human beings and not only as study “subjects.” These real world skills one has to acquire with compassion and caring. Roger Detels succeeded where others had reached a dead end due to the wall of discrimination which he was able to pull down.

Key Takeaways

In chess, the “hardest thing is to win is a won game,” as stated by an artist of the game, Emanuel Lasker, a mathematician, philosopher and World Chess Champion for 27 years. Similarly, as we are nearing the end game of winning the war against AIDS, the struggle is going to be tougher. We may have the winning piece, the ART, but like in chess the other pieces and their combination with each other keep changing constantly and matter equally, if not more.

We need to explore all the social factors that may be contributing to the rising trend—social pathology, in particular—and involve social scientists to identify social therapies and empathies aimed at removing stigma and discrimination, crucial factors for pushing the epidemic underground.

(The author is a Professor of Community Medicine and Clinical Epidemiologist at Dr. DY Patil Vidyapeeth, Pune