Waiting for a Lifeline

An estimated two people in India die from kidney failure every five minutes. While kidney transplantation stands as the definitive treatment, a profound deficit in organ donors leaves countless patients suspended between the sustaining drain of dialysis and the distant promise of a transplant.

By Abhigyan/Abhinav

In India, the escalating crisis of kidney failure presents a devastating public health challenge. According to the latest data, 2024 saw a significant surge in chronic kidney disease (CKD) cases, imposing an immense burden on the nation’s healthcare infrastructure. With the World Health Organisation (WHO) classifying advanced kidney disease as a ‘serious condition’, it is imperative for medical professionals and the public alike to understand its root causes and the urgent need for systemic solutions, particularly in expanding access to life-saving kidney transplants.

CKD and its most severe form, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), are profoundly prevalent in India, with millions of patients in dire need of kidney transplants. Indeed, kidney transplants are the most frequently performed organ transplant in the country, accounting for nearly 70 per cent of all procedures. However, this figure belies a grim reality: the availability of donor kidneys is critically limited, creating long waiting lists and a cavernous gap between demand and supply. A report reveals that although the total number of organ transplants in India has significantly increased from 4,990 in 2013 to 18,378 in 2023, and further to an estimated 18,911 in 2024, the organ donation rate remains dismally low at less than 1 donor per million population. This shortage translates into an ongoing humanitarian crisis where access to transplantation is often a matter of chance or means.

Understanding the Causes of Kidney Disease

The silent progression of kidney disease makes it a particularly insidious threat. A staggering statistic underscores its lethality: an estimated two lakh people die from kidney-related diseases in India every year, equating to roughly two deaths every five minutes. The urgent need is to establish widespread detection clinics and implement preventative strategies to arrest this tide of mortality.

Most people are unaware that kidney disease can be a silent killer, often showing no overt symptoms until the situation becomes critical. Early signs can be subtle, including changes in urination patterns—such as an increase or decrease in frequency, especially at night, or darker coloured urine. A person may feel the urge to urinate but find themselves unable to do so. The most common drivers of kidney disease are diabetes and high blood pressure, both of which damage the kidneys’ delicate blood vessels over time. Arteriosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries, also contributes to this damage.

Other kidney diseases arise from different mechanisms. Nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys, can result from infections or autoimmune reactions where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own renal tissue. Anatomic disorders, such as polycystic kidney disease, affect the kidneys’ size and structure, while metabolic disorders interfere with their inner workings; these latter forms are often inherited and relatively rare. The kidneys, two bean-shaped organs located beneath the ribcage, perform the vital function of filtering waste products from the blood to form urine. When they lose this ability—a state known as kidney failure—a transplant becomes the most viable long-term treatment option for survival.

Why Transplantation is the Optimal Need

For a patient with renal failure, a kidney transplant is not just a procedure but a lifeline. Beyond dialysis, which is a sustaining but burdensome treatment, transplantation is the only avenue for someone with advanced renal failure to regain a good quality of life and long-term survival. A successful transplant requires a healthy, immunologically matched donor. Even after a transplant, the recipient must commit to lifelong immunosuppressant medication and continuous medical supervision to protect the new organ.

A kidney transplant can be considered for recipients of almost any age, provided their overall health is robust enough to withstand major surgery and they are willing to adhere strictly to post-operative care regimens. Dr Rajesh Aggarwal, Chief Nephrologist at Sri Balaji Action Medical Institute, explains the threshold for intervention: “We use a test called the creatinine clearance to measure kidney function. When this clearance falls to 10-12 cc/minute, it indicates the kidneys are failing to a point where dialysis becomes necessary.” Creatinine, a waste product from muscle metabolism and protein digestion, is normally filtered by the kidneys. Elevated levels in blood tests are a key indicator of impaired renal function.

The Transplant Procedure and Post-Operative Journey

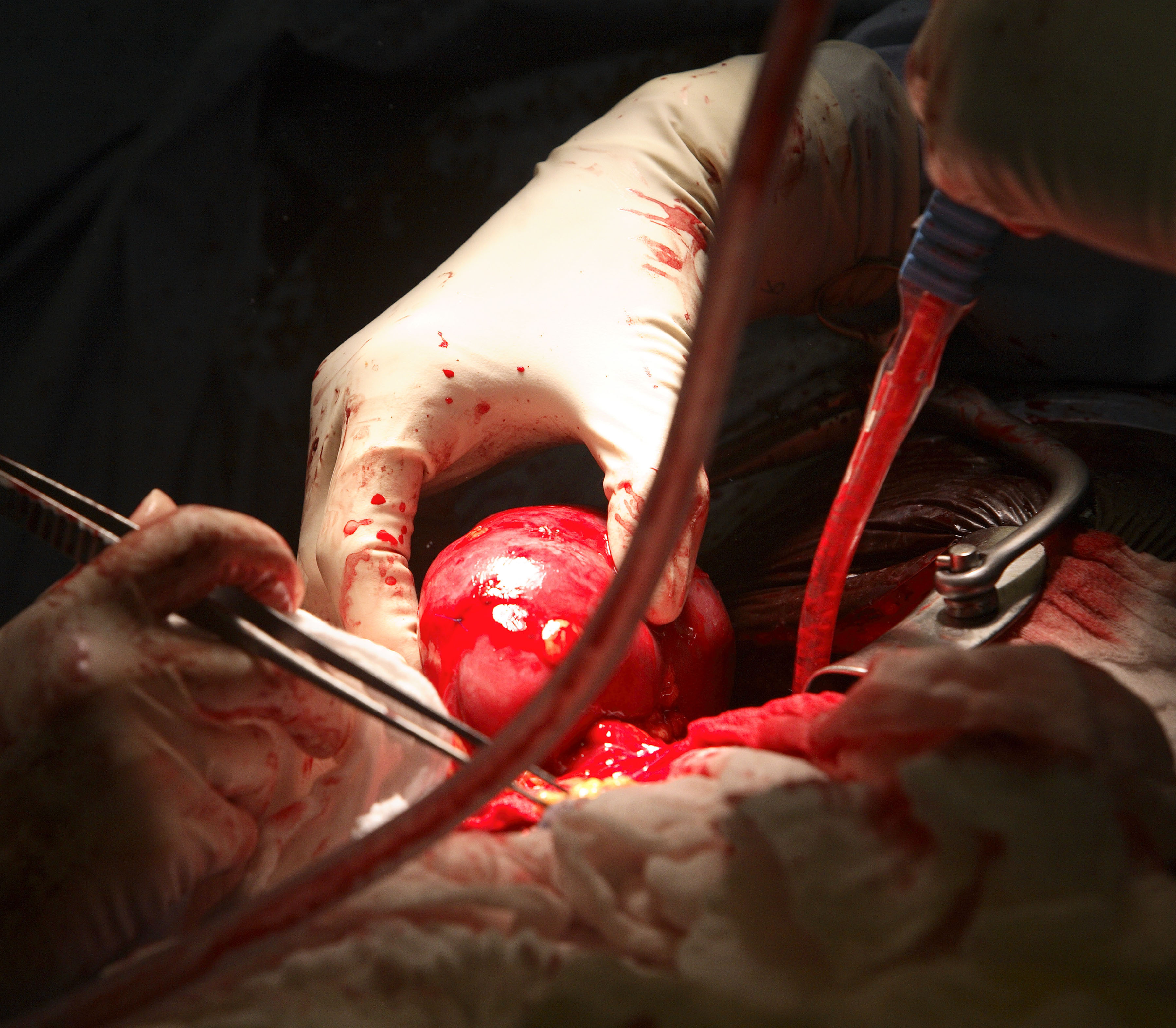

The transplant surgery itself typically lasts about five hours. The donor kidney is placed in the recipient’s lower abdomen, where its blood vessels are meticulously connected to the recipient’s arteries and veins. Once blood flow is restored, the final step is connecting the donor kidney’s ureter to the bladder. In most cases, the new kidney begins producing urine almost immediately. Living donor kidneys generally take 3–5 days to reach normal function, while kidneys from deceased donors may take 7–15 days. The average hospital stay post-transplant is 4–7 days, though diuretics may be administered if needed to encourage urine production.

The cornerstone of post-transplant care is immunosuppression—drugs that suppress the recipient’s immune system to prevent rejection of the donor organ. These medications must be taken for life, with blood levels monitored closely. Complications can arise; for instance, grapefruit and certain other citrus products can interfere with drug metabolism and must be avoided. Acute rejection, occurring in 10–25 per cent of patients within the first sixty days, does not always lead to organ loss but requires prompt treatment and medication adjustment.

Potential post-transplant challenges are multifaceted. They include various forms of rejection (hyperacute, acute, or chronic), infections and sepsis due to immunosuppression, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (a type of lymphoma), electrolyte imbalances affecting bones, and medication side effects ranging from gastrointestinal issues to hirsutism, hair loss, obesity, acne, and new-onset diabetes or high cholesterol.

Addressing the Donor Shortage

The severe shortage of kidney donors remains the most critical barrier, causing immense suffering for those on waiting lists. In this context, groundbreaking medical research offers a glimmer of hope. A landmark study from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States has demonstrated that kidney transplants between HIV-positive donors and recipients are as safe and effective as those involving HIV-negative individuals. This discovery, as noted by Dr Suriraju V, Senior Consultant Urologist at Regal Hospital, “could transform kidney transplants in India. With such a large number of patients suffering from renal failure and the severe donor shortage we face, the possibility of expanding the donor pool through such practices could be a lifesaver for many.”

Policy innovation is also crucial to optimize the system. Proposals to increase overall transplant benefit focus on better matching donor kidneys with recipients. The Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) is a clinical formula that predicts how long a donor kidney is likely to function. Allocating kidneys based on such metrics, and calculating waiting time from the start of dialysis, can help address two key problems: ensuring that kidneys from ideal donors go to recipients with long expected survival, and that less-than-ideal donors are used effectively for recipients with appropriate life expectancy.

The Indian Transplant Landscape

India ranks third globally in total organ transplantation volume, after the United States and China, and holds the top position for living donor transplants. In 2024, there were 13,476 kidney transplants performed nationally, with the highest numbers in Delhi, followed by Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, and West Bengal. The annual report by the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO) also highlighted Tamil Nadu and Delhi as leaders in multi-organ transplants.

However, the system is marred by significant challenges. Over the last 10 to 15 years, organ donation in India has been hindered by stigma and illegal practices. The Transplantation of Human Organs Act (1994) prohibits commercial dealings in organs, yet the high demand has fuelled a black market, with periodic scandals involving the exploitation of economically vulnerable individuals. Dr S P Yadav, a Senior Urologist and Member of the Medical Council of India, New Delhi, emphasises the need for systemic reform: “There should be a uniform legislative policy to augment organ donations and enforce regulatory mechanisms. Kidney transplantation is different from other healthcare activities, and the law on this subject should be strengthened by the Centre.”

Dr Yadav advocates for a centralised regulatory authority with pan-Indian jurisdiction to monitor procedures, inspect hospitals, and maintain mandatory registries of all transplants. “All transplantations must be registered, which should allot a wait-listed number to each registrant,” he states. This contrasts with international models, like in the Netherlands, where organ donation education is integrated into school curricula, and over 80 per cent of transplants are from deceased donors.

The Path Forward

The path to resolving India’s kidney transplant crisis is multifaceted. While medical advancements promise better outcomes—with one-year graft survival rates now at an impressive 95 per cent—the bottlenecks begin with the ever-growing waiting list. Dr Rajesh Agarwal of Sri Balaji Action Cancer Hospital notes the duality of progress and persisting fraud: “Kidney transplantation in India faces great challenges in the wake of acute organ shortage and difficulty to optimise transplant outcomes… Then there are fraudulent practices giving a fillip to the growing market in illegal organ transplant.”

Ultimately, enhancing public awareness about legal organ donation, strengthening ethical and transparent regulatory frameworks, and embracing medical innovations like HIV-positive donor protocols are essential. The goal must be to build a system that serves all equitably, transforms the pledge of donation into a cultural norm, and ensures that no patient dies waiting for a second chance at life. The kidney transplant, while not an emergency surgery thanks to dialysis, represents the definitive restoration of health and dignity—a lifeline that must be made accessible through concerted national effort.